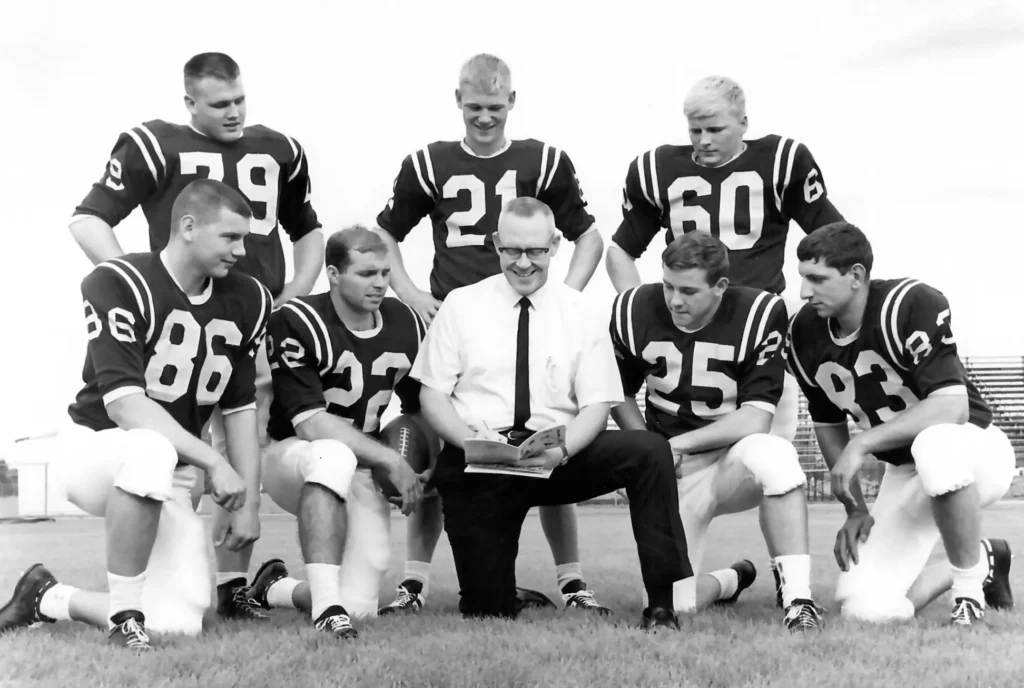

“Roy’s boys” were his real scoreboard, and they never left him

Roy Kramer could explain the machinery of college sports as well as anyone who ever sat in a commissioner’s chair.

He helped shape big decisions, navigated powerful rooms, and watched the game change around him.

But when he talked about what mattered most, he didn’t start with expansion or television or titles.

He started with a classroom and a small-town field, and the simple plan he once had for his life: “set out to be a high school football coach” and to “teach American history.”

The longer he coached, the more the job became something bigger than football.

“One of the great things about coaching, you can’t take that away,” Kramer told Jimmy Hyams on The Rewind on Full Disclosure. Winning was part of it, he acknowledged, but it was not the part that endured.

“The great part about it is they become your family,” he said.

Kramer’s coaching life began after the Army, buoyed by the GI Bill, when he went north to the University of Michigan to get a master’s degree and “ended up getting off for a job in Battle Creek Michigan as freshman JV football coach and a history teacher.”

It was the sort of beginning so many coaches recognize: a whistle, a gradebook, and a group of young men learning how to be accountable to something outside themselves.

He smiled at how fragile success could be in high school, where you don’t recruit and you’re never far from the roster reality. He once went undefeated, then looked ahead and made a quick, practical decision.

“Everybody was a senior so I figured I better get out of town,” Kramer said. He delivered it without drama, with a slight laugh. Just the honest math of a coach who understood the job.

“In high school you don’t recruit so you’re kind of a victim of how the genes were running 16 or 17 years ago.”

Even his career moves carried the imprint of place and people.

Two high school offered Kramer jobs on the same day.

He and his wife, Sara Jo, drove to see both towns, looking for something that felt like home and football at the same time.

In one place, he had to ask around to find the stadium to no avail.

In the other, he walked into a drugstore and asked the pharmacist and got an answer that told him everything; pride, proximity, and the way a community stitched itself together on fall nights.

“I came out and I said, ‘Sara Jo, I think we’re going to the W,” he recalled. She asked why. Kramer’s answer was quick and affectionate, the kind of line that sounds like a joke until you realize it’s a measuring stick.

“Because the farmers knew where the football stadium was,” he said.

Kramer later spent 11 years at Central Michigan, a run that included a national championship in 1974. Yet he talked about his coaching legacy in the way coaches usually do when they’re telling the truth: not in trophies, but in people.

“Roy’s Boys is just a group of good old guys that played for me,” he said. “Probably didn’t like playing for me at all, but that brought them together I think because maybe they hated me.”

He said it with humor, but the affection underneath it was unmistakable.

The group didn’t dissolve with time the way so many teams do. They stayed connected, not as a nostalgic mailing list, but as men who still choose each other.

“They still get together,” Kramer said. “They go up north fishing and hunting and have a get outing and so forth and that still gets together.”

It’s a simple image, and an honest one: the yearly pull back toward the same circle. Kramer didn’t claim he created that bond on his own. He just spoke like a coach grateful to have been part of it.

“One of the great things about coaching is you can’t take that away,” he said again, returning to the point the way people do when they’re talking about something they’ve carried for decades. “The great part about about it is they become your family.”

Kramer admitted he missed coaching after leaving it in 1979. “Yes cause you know you miss that part of it,” he told Jimmy Hyams on The Rewind on Full Disclosure.

He didn’t talk about missing the spotlight. He talked about missing the closeness, the daily trust the way players lean on a coach for more than football.

“The day-to-day contact you know they come to you with every kind of problem that exists,” he said. “You miss that once you get out of coaching.”

“You try to keep it up but you can’t,” Kramer said. “You’re not, you’re not at that same level.”

Still, the connection endured. “They never leave you,” he said. “I hear from them. They come by and see me.”

Then he landed on the line that carried the weight of the whole profession, the time capsule every long-time coach keeps in his chest.

“To me they’re still about 19 or 20 years old,” Kramer said.

The sport changed around him, and his roles changed with it. But the thing he sounded most certain about wasn’t money or power or prestige. It was the part of the game that outlasts the games.

“It’s a great feeling that’s there,” Kramer said. “One of the greatest rewards of coaching is that part of the game.”

And in the end, that was the thread running through his life: the young men who once called him coach, now grown, still circling back and still, in his mind, not much older than 20.

This article was brought to you by Jimmy Hyams’ interview with Roy Kramer on The Rewind on Full Disclosure.